Down to Earth

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

According to the theory supported by scientists, the Moon and Earth have two similar chemical compositions. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the two celestial bodies are thought to have actually been generated by one. In particular, according to this assumption, known as the Giant Impact Hypothesis, our satellite appears to have formed during the impact of a huge celestial body against our planet. From this impact the Moon was formed, which after this impact began to rotate in orbit at a distance of about 385,000 km from the Earth. According to these theories, on our satellite there could be deposits of precious materials – partly already present on earth but in smaller quantities – such as rare earths, fundamental for today’s electronics, or other metals or materials such as titanium, gold, platinum and helium-3. The latter is a stable helium isotope that could be used for nuclear energy. That image of fascination, mystery, beauty and white purity which for millennia has linked the Moon to man’s imagination, now seems to have been replaced by the less romantic one of an enormous mine from which to obtain priceless sources of energy and wealth.

This shift in the exploitation of energy sources from the Earth to other planets, celestial bodies, asteroids and therefore also our satellite requires the urgent opening of a debate on the impact that this reorientation will have on our conception of soil, resources and goods common. With the Down to Earth exhibition, Luxembourg takes part in the Venice International Architecture Exhibition with an installation that seems to respond provocatively to the title – The Laboratory of the Future – of this 18th edition curated by Lesley Lokko – bringing into the Sala d’Armi dell’Arsenale, a real “lunar laboratory” for a future that doesn’t seem so distant.

The Luxembourg Pavilion at the Venice Biennale poses the problem of the earth’s resources at various scales, but above all it poses the problem of the future world that we are creating by pushing beyond the limits of the spaces colonized and exploited by man beyond the Earth. To learn more about the contents and aims of the exhibition, Nicola Desiderio (Arcomai’s Editor-in-chief) has met the two curators of the exhibition Francelle Cane and Marija Marić, both architects and researchers at the University of Luxembourg.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

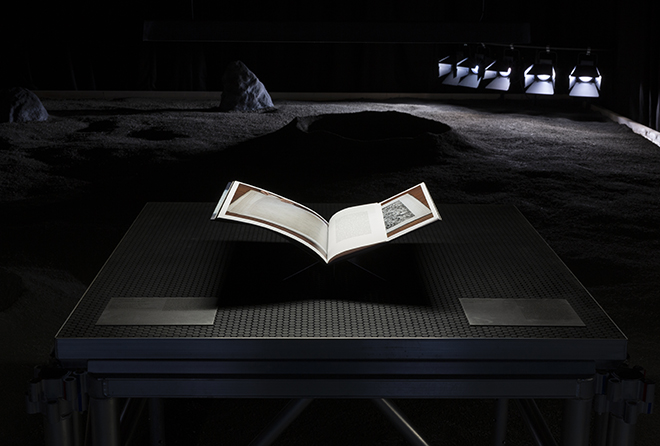

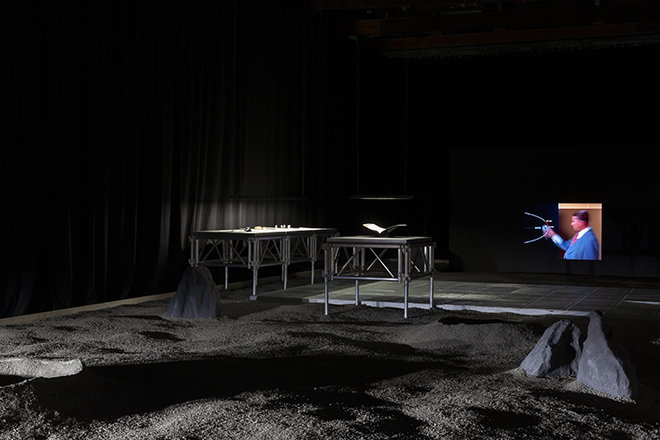

N.D. The Down to Earth installation is the mockup of a lunar laboratory developed on the basis of the specifications of similar lunar laboratories under study and construction. The lunar surface was created using a 7 cm deep and perfectly sealed pine wood tub filled with basaltic earth and artificial rocks. Visitors can walk around it to view the “Moon’s surface” and view a movie (in English), created in collaboration with the artist Armin Linke, which collects footage, archival materials and conversations with researchers, artists, representatives of the mining sector in the space and/or other organizations based in different countries, including Luxembourg, and beyond. Could you tell us more about the design and realization of your installation? Besides, would you mind to give us more details about the contents of the visual materials?

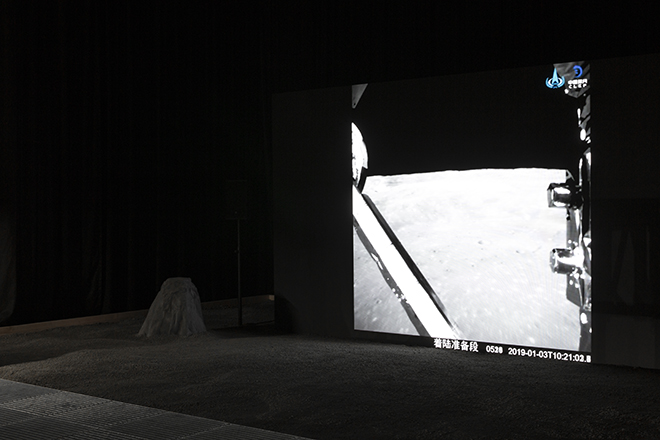

F.C & M.M. The development of lunar laboratories—following the privatisation of the space research sector, which has been occurring over the past decade—and their construction as an infrastructure for testing space mining technologies seems to have become today a default feature in different institutions and organisations around the world. In the course of our research, we realised that the economy around the space mining industry was very speculative and heavily relied on the staging of techno-fix narratives and resource fiction, and that the construction of lunar laboratories was a way of basing this new industry on a tangible visual and physical backdrop. It became thus clear that lunar laboratories are not facilities meant solely for testing space mining technologies but that they also serve as media studios, constituting the stage where the imagery of man-made technologies on the Moon is being produced.

This two-fold feature of the lunar laboratory typology became the starting point of our installation. The characteristics of our lunar lab are present as follows: a lunar surface simulated by basaltic sand, fake rocks, and craters; a sealed tub containing this landscape as well as black curtains enclosing the installation and a row of lights, placed close to the ground, suggesting the lighting conditions that would be present on the Moon, which is also featured in the labs we visited. But, rather than using this lunar laboratory as a stage, on which the performance of extraction would usually take place, we used it as a setting to critically unveil the backstage of the space mining project: we have developed three projects, which constitute fragments of the exhibition that aim at offering another way of seeing the Moon, including a film that you were talking about, but also a workshop and a book. All three are displayed in the lab and accessible via a walkable steel platform allowing visitors to enter the scenery and have a closer look at each piece.

Back to your question on the movie by photographer and video artist Armin Linke. The film is entitled Cosmic Market and is the result of filming made between November 2022 and February 2023 at historical observatories and archives in Italy, as well as in institutional and private stakeholders of space exploration in Luxembourg. Together with Armin, we visited laboratories and sites of technological experiments and conducted conversations with scientists, companies, and legal experts involved in space mining project. The whole takes the form of an artistic collage of interviews interspersed with mapping, operational images, and archival material—mainly footage from the 20th century from a Cold War context. In a nutshell, it is a project that exposes connections between scientific research and differing interpretations of space legislation, as well as between technological development and the establishment of what we call a new ‘cosmic market’ that is growing both on Earth and beyond.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

N.D. Down to Earth also includes a workshop, happened at the beginning of the year and entitled How to: mind the Moon, which you curated and developed in collaboration between the Luxembourg Pavilion, and the Canadian Center for Architecture, joined by an international group of researchers engaged in the history of materials or space settlements, including: Anastasia Kubrak, Jane Mah Hutton, Amelyn Ng, Bethany Rigby and Fred Scharmen. The result of the workshop forms a materials database, with the political, environmental and racial histories of five lunar materials. How was the workshop structured? What was the main outcome of the collected material and how did this research feature in the making of the exhibition?

F.C & M.M. How to: mind the moon was developed in collaboration with the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA) and Lev Bratishenko—who was then Curator Public at the CCA. Our workshop took place over two weeks and was held online. We invited a small multidisciplinary team constituted of the five participants you mentioned—who either are architects, landscape architects, or artists—who already had a research background on earthly and non-earthly materials, or broader outer space issues. We decided to work within the formats of the material datasheet and material sample—following the example of the technical documents used in materials science that define chemical or mechanical properties. Starting from this, we asked each participant to choose one lunar material to work with and to critically distort these given formats. The main rule concerning the material sample was that it could take the form of any medium (video, photo, text, recording, physical object, etc.) except a literal representation of the chosen material. We wanted this workshop to explore how tools of extractivist vision, such as geological and technical material datasheets could be perverted to new ends in order to develop what we call another kind of material library. The goal was to outline another way of reading these lunar materials, with a content that goes beyond the apparent scientific neutrality claimed by materials science.

The five collected lunar materials were: regolith (Jane Mah Hutton), the lunar dust (Amelyn Ng), solar wind (Bethany Rigby), the seconal sodium (Anastasia Kubrak), and the aluminium (Fred Scharmen). As a result, the workshop takes the form of the material library that we mentioned, within the exhibition as well as on the CCA’s website, where each material is presented together with its datasheet and sample. The whole frames the materials’ political, social, environmental, and cultural conditions, both as a physical matter and a form of fiction. Like the film and the book, the workshop is a fragment of the overall research, one more opportunity to learn more about the intricacies of the subject from fascinating discussions with geographers, scientists and even space archaeologists, whom we invited to join some of our sessions.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

N.D. Staging the Moon: Resource Extraction Beyond Earth is a book that includes contributions from the curators and a selection of photographs by Armin Linke and Ronni Campana. The publication is part of the exhibition and presents the curators’ research on the topic of mining in space, which revolves around topics such as the intertwining of mining in space and the media, the development of legal frameworks on mining in outer space, and the possibilities of planetary commons. It is designed by OK-RM studio (London, UK) and published by Spector Books (Leipzig, Germany). Since the book is available for purchase at the Biennale’s shop, how would you describe ‘Staging the Moon’ to someone who hasn’t had the chance of viewing the exhibition? What would you say is the core message of the book?

F.C & M.M. The book is the third and last fragment of research that is accessible to everyone visiting the exhibition—and anyone can also browse through it. Staging the Moon: Resource Extraction Beyond Earth critically unpacks the industrial space mining project by bringing together essays and visual works that challenge the way of looking at the Moon (and other celestial bodies) as the new resourceful frontier. Its structure echoes the one of the exhibitions, establishing the relationship between the stage and the backstage once again: Ronni Campana’s photographic work deconstructs each element of the lunar laboratory (stage) when Armin photographs and shows the places, the objects, or the tools that constitute the environment in which the project develops (backstage). The essays written by the two of us reflect on the ambiguous legal framing of the notions of lunar soil and the cosmic commons, as well as on the infrastructural power of the New Space Age media in legitimising and naturalising mineral extraction (backstage). The book aims—as much as does the exhibition—at reflecting and challenging the current status quo around resource exploitation on Earth and the one yet to be expanded beyond, and to look at the Moon as a subject and not an object, a comrade which we share the same struggle of the capitalism’s extractivist logic with. As a note, this publication is not really the exhibition catalogue but more like a standing piece that is part of the exhibition with its own status, as the workshop and the film are also in the end.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

N.D. Luxembourg, despite being nicknamed the “Green Heart of Europe”, has a highly industrialized and export-intensive economy, linked to iron mining and steel production. which helps to guarantee an unparalleled degree of prosperity among industrialized democracies with a per capita gross domestic product that is second in the world, after Qatar. But Luxembourg’s economy is also largely based on the banking sector. Therefore, we are talking about a unique country in the world, characterized by a small territory compared to the other members of the European Union. but of global importance. For these characteristics, it stands as a fundamental starting point for critically addressing the mining activity in space – an issue that goes well beyond the dimensions of its territory and which presents itself, instead, as a common planetary concern. Since Luxembourg has also appeared as one of the leaders of this new interest in space, which role do you think your country will play in this rising space industry?

F.C & M.M. Indeed, Luxembourg is already an important international stakeholder engaged in the space mining project but has also been more broadly engaged for a while now in outer space activities. In the 1980s, in its transition from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy after the decline of steel production from the mid-1970s, the Luxembourg state launched a satellite telecommunications network provider named SES (Société Européenne des Satellites) that became and stays nowadays one of the world’s prominent operators. Luxembourg has therefore been building its ‘spatial connivence’ for some time. More recently, less than ten years ago along with the US, Japan and the UAE, it was one of the first countries to start providing legal frameworks that would allow institutions and private companies operating from the Luxemburgish territory to develop research projects in relation to material extraction in outer space. Since then, numerous local and international private companies have set up their headquarters and operations on the territory, the European Space Agency created and implemented its Space Resources Innovation Centre (ESRIC) a few years ago, and a major Space Campus bringing together ESRIC and the university’s Master in Space that should enter into operation in 2026 is being built next to it. The institutional will to make Luxembourg an international hub for outer space research on extraction and business is undeniably present, and if things go as it is planned, then it is likely to happen. Since Luxembourg is already such an important place for space mining industry, our project tried to frame Luxembourg as a place where debate and discuccion on space mining could also take place.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

N.D. Through the Agenda 2023, the United Nations urges architects, engineers, and urban planners to put the principles of sustainability into practice. Agenda 2030 is one of the main topics present at this Biennale of Architecture in Venice as well as in the ongoing architectural debate worldwide. In light of this rase to space mining, do you think the Lunar colonization could affect the Agenda’s goals?

F.C & M.M. We believe that it is an illusion and a simplistic approach to think that exploiting resources ‘elsewhere’ will solve the problems of extracting and using resources on our planet on the pretext that it would be ‘cleaner’ or ‘greener’. Regardless of the location, the issue of resource exploitation is indissociable from the questions of sustainability, social equity, and economic development that are part of the 2030 UN Agenda. We now all know the devastating human, environmental, and political consequences of mineral extraction. And relocating extraction sites will not solve the problem, because it is part of the continuation of this exploitative model. This leads us back to the title of the exhibition, Down to Earth, which calls on us to question, reconsider, and eventually change the relationship we have with the Earth’s resources that we already have, rather than looking again and again for new sites of destruction.

© Antoine Espinasseau I Down to Earth.

Biographies of curators

Francelle Cane is an architect, researcher and curator based in Luxembourg. She has been a doctoral researcher at the Chair of Urban Regeneration, University of Luxembourg, since 2021. Her research explores the subject of ruin through the perspective of soil, thus reshaping the relations between the built environment, policies and soil ecologies. For several years, her practice has involved various collaboration types and project formats, including curating and designing exhibitions as a means of research. Cane is the author of Machine opérationnelle (FWB, 2021), The World as a Pavilion. Vjenceslav Richter (Koenig Books, 2020, with Vesna Meštrić and Iwan Strauven), and Enter the Modern Landscape (Bozar, 2019, with Axel Fisher and Iwan Strauven).

Marija Marić is an architect, researcher and curator based in Luxembourg. She works as a postdoctoral research associate at the Master in Architecture programme, University of Luxembourg, where she also teaches. In 2020, she obtained her doctoral degree from the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zurich, with research examining the role of media strategists in the communication, design and globalisation of urban projects. Marija’s work has been presented and published internationally. Her research is organised around the questions of resources, real estate, media, and the production of the built environment and its imaginaries in the context of global capitalism and the global flow of information.